Research ProjectMovement of Life Initiative

Affiliated Labs

Project Goal

The goal of the Movement of Life Initiative is to develop the science, technology, analytical tools and models to conserve and manage movement as a critical process for maintaining biodiversity and healthy ecosystems. At SERC, we focus on coastal fish and invertebrates and their connections with freshwater and the open ocean.

Description

Many species on the planet migrate during their lifetime, using different habitats in different areas for different reasons at different times. But what are those areas? Which are most important? What are they used for? Our lab is interested in learning more about migratory species, and currently our projects focus on species that move in and out and around east coast estuaries and along the Atlantic Coast. Our lab employs various tracking techniques, including mark and recapture and acoustic telemetry, in order to gain insight into the behavior and migration. Learn more about the Movement of Life Initiative.

The Atlantic Cooperative Telemetry (ACT) Network is a grassroots initiative of researchers on the Atlantic coast of North America facilitating the use of acoustic telemetry for science and natural resource management. Our lab coordinates and manages data for the ACT Network, including development and implementation of the next generation acoustic telemetry database, the ACT Network data portal. This database features improved data management and quality control, automated data sharing with other regional and global databases, and long-term data archiving. We also coordinate an annual network meeting, training sessions for data management and analysis, and social media and other outreach efforts. By working together, the ACT Network is increasing our knowledge of marine species and ecosystems and translating that information for the public and policy makers to support management and conservation.

More information on the ACT network can be found here: https://www.theactnetwork.com/

ACT Network data portal: https://matos.asascience.com/

Coastal Shark Habitat Use and Migration

Video edit by Cosette Larash and Claire Mueller

Project Goal

Our goal is to use telemetry methods to better understand habitat use and migration behavior among coastal sharks in the U.S. Mid-Atlantic region by identifying habitat areas within the Chesapeake Bay estuary, describing migratory connections between the Bay and other parts of the coast, and using this information to predict how coastal shark movements might respond to large-scale environmental changes.

Description

The U.S. Atlantic Coast is one of the global hotspots of shark and ray biodiversity. These ancient species play critical roles in sustaining healthy marine and estuarine ecosystems, but many aspects of their ecology remain to be discovered. Our lab is working to understand the diversity of shark and ray movement and habitat use behavior using animal telemetry technology to track the habitats of multiple species. As the largest estuarine ecosystem in the United States, the Chesapeake Bay and surrounding Atlantic Ocean waters contain a wide variety of potential shark habitats. Tracking sharks within and outside the Bay will allow us to answer the following questions:

- How do coastal sharks make use of habitats within the Chesapeake Bay and adjacent continental shelf, and divide or share these habitats between species

- Where else do sharks tagged in or near the Chesapeake Bay travel to over the course of their annual migrations

- Can we use this information to predict how coastal shark movements, habitat selection, and interactions with other species might be affected by climate change and other large-scale environmental shift

Our target species occur regularly in the Chesapeake Bay region and fulfill a variety of ecological roles, but much of the basic information about their movement ecology within the estuary and beyond is still unknown. These species include bull sharks capable of moving into brackish and freshwater habitats, blacktip sharks that form packs to attack schools of pelagic fish, slow-growing dusky sharks that are vulnerable to extinction, and smooth dogfish that feed on crustaceans and support a commercial fishery.

For more information on the sharks we'll be tracking, see the species profiles below.

Smooth dogfish

Smooth Dogfish – Mustelus canis (also known as the dusky smoothhound)

Habitat – The smooth dogfish is a temperate species native to the east coast of North and South America. In more temperate waters smooth dogfish occur near shore and within estuaries, occasionally entering brackish water. South of South Carolina and within the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean smooth dogfish inhabit deep waters on the edge of the continental shelf. In the Chesapeake Bay region these sharks can be very common near shore and relatively far up the bay.

Size – Smooth dogfish are a small to mid-sized shark, reaching total lengths of nearly 5 feet but are usually 3.3 feet or less in length. Juvenile smooth dogfish are born slightly more than one foot long.

Ecology – Smooth dogfish are bottom-dwelling but active sharks of nearshore and estuarine waters. Though they will occasionally feed on small fish, Smooth Dogfish are primarily predators of crustaceans. In the Chesapeake Bay region their prey species include rock crabs, blue crabs, mantis shrimp, Atlantic brief squid, small summer flounder, scup, and mummichogs. Smooth dogfish are most active at night and will form groups around sources of food. Smooth dogfish will also form schools with other small sharks such as the similarly-named but distantly-related spiny dogfish. Juveniles are born in shallow marsh estuaries and adults will also enter estuaries to feed. Smooth dogfish have a faster growth rate and higher reproductive output than most other coastal sharks, reaching reproductive maturity between the ages of four and five.

Research Significance – The smooth dogfish is the second most-landed shark species in U.S. commercial fisheries but did not have a fishery management plan until 2015. This species was historically regarded as a nuisance and has only recently been prioritized as a research subject. Knowledge of their movements in estuaries is limited and even less is known of their larger-scale coastal migrations. As mid-level predators on primarily benthic prey, smooth dogfish are different ecologically than most other sharks in the Chesapeake Bay region. Tracking smooth dogfish may document movements in response to prey availability that can determine their potential impact on economically-important crab and shrimp species. Smooth dogfish are also themselves prey for larger sharks, and their movements may also reflect their responses to the presence of other shark species tagged by the Movement of Life Initiative.

More Information

Dusky shark

Dusky Shark – Carcharhinus obscurus

Habitat – Dusky sharks occur in temperate to tropical waters worldwide. They are very much a coastal species, occurring relatively close to shore but only rarely entering estuaries. Some individuals have been tracked moving offshore to the continental shelf break. In the Chesapeake Bay region both adults and juveniles can be found near the mouth of the bay and along the beaches, but rarely occur farther within the bay than the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel.

Size – Dusky sharks are among the largest coastal sharks and the largest species in the genus Carcharhinus, reaching nearly 14 feet in length. Most individuals are 8.2 feet in length or less. Dusky sharks are born larger than most other coastal sharks, with a length-at-birth of 2.5-3.3 feet.

Ecology – Dusky sharks are large, slow-growing apex predators of coastal waters. They are born large enough to pose a predatory threat to other juvenile sharks, which are included among their prey. Dusky sharks near the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay prey upon skates and stingrays, bluefish, summer flounder, weakfish, monkfish, and spot. Adults are large and powerful enough to feed on sea turtles and marine mammals. Dusky sharks are among the most slow-growing of shark species, not reaching reproductive maturity until they are 17-26 years old and over 7.2 feet long. This slow growth has made them vulnerable to overfishing and populations in U.S. Atlantic waters may be as low as 15 % of their original numbers. Juvenile dusky sharks tend to occur in the same areas as juvenile sandbar sharks, and both species overwinter in large numbers off of Cape Hatteras on the North Carolina coast. During the summer these species separate as sandbar sharks move up into estuaries while dusky sharks remain in the ocean.

Research Significance – Dusky sharks are among the species most affected by human activity and a number of conservation measures have been introduced to rebuild their population in U.S. waters. Despite a ban on fishing for this species and the establishment of a protected nursery area off of North Carolina, accidental bycatch of juvenile dusky sharks remains high enough to slow population recovery. One challenge is a lack of basic knowledge about dusky shark habitat use and movement patterns, especially among juveniles. Tracking dusky sharks will allow for identification of important habitat areas and environmental conditions that can be avoided by fishermen trying to avoid catching them. Dusky sharks are also apex predators and information gathered on their interactions with other prey and competitor species may allow researchers to predict how other species will react to changes in the dusky shark population.

More Information

Blacktip shark

Blacktip Shark – Carcharhinus limbatus

Habitat – The blacktip shark inhabits warm-temperate and tropical waters worldwide. This species occurs near shore and within estuaries, though they prefer to remain in higher-salinity parts of the estuary closer to the ocean. Blacktip sharks migrate into the Chesapeake Bay region during the summer, occurring close to shore near Virginia Beach and the Eastern Shore, within the coastal lagoons along the Eastern Shore, and within the lower Chesapeake Bay.

Size – Blacktip sharks can reach 9 feet in length, though most are 6 feet or less. Juveniles are 2-2.5 feet in length at birth.

Ecology – The Blacktip shark is an active and social species. Huge schools of migrating blacktip sharks have been photographed from the air off of Florida, where they overwinter. In the spring they migrate northward through North Carolina and Virginia waters and have been documented as far north as Long Island during warmer than average summers. Another mass migration occurs during the fall as the sharks return to southern Florida and Caribbean waters. Blacktip sharks feed very actively and can be seen making spinning leaps out of the water as they chase prey. Their primary prey species are schooling fishes such as Atlantic menhaden, striped mullet, spot, and Atlantic croaker, though they will also feed on larger prey such as red drum, Spanish mackerel, small coastal sharks including Atlantic sharpnose and bonnethead sharks, and cownose rays. Blacktip sharks give birth in southern estuaries from South Carolina to Florida, where the juveniles take shelter from larger sharks in shallow water.

Research Significance – Blacktip sharks are among the most mobile species occurring in Chesapeake Bay, and tracking their movements may reveal which factors bring this wide-ranging species into the estuary and help identify other important stops as they travel along the U.S. East Coast. Blacktip shark migrations are thought to be driven by ocean temperatures and the movements of their prey, both of which may be altered by climate change. Tracking their movements may show evidence for climate-driven range shifts, and may also show relationships with the movements of their prey.

More Information

Bull shark

Bull Shark – Carcharhinus leucas

Habitat – The bull shark is an apex predator of near shore and estuarine environments in warm-temperate and tropical waters worldwide. Bull sharks are able to enter freshwater and have been found up to 1,700 miles up the Mississippi River, 2,400 miles up the Amazon River, and even living in a landlocked water hazard at an Australian golf course. Bull sharks are summer visitors to Chesapeake Bay, occurring from late June through September. Within the Chesapeake Bay, bull sharks are most often encountered from the ocean to the mid-bay and within the Potomac River and Tangier Sound, but they have been found all the way up the estuary near the mouth of the Susquehanna River.

Size – The maximum confirmed length for this species is 13.2 feet, though most are 8.5 feet or less. Females grow larger than males. Bull sharks are 2-3 feet in length at birth.

Ecology – The bite of a bull shark exerts more force than a similarly-sized white shark, and this species feeds on other large marine animals like sharks (including cannibalism on other bull sharks), marine mammals such as seals and dolphins, sea turtles, and large fishes, occasionally taking prey nearly as large as themselves. Bull sharks captured in the Chesapeake Bay have been documented feeding on a variety of marine and anadromous species including American eel, striped bass, summer flounder, cownose ray, weakfish, red drum, and Atlantic croaker. These sharks may also prey on freshwater fish species. Bull shark movements and migrations are not well understood, but they have been tracked making regular long-distance movements between reef sites, along shorelines, and into estuaries and rivers. However, pregnant female bull sharks may return to give birth in the same nursery habitat where they were born. Juvenile bull sharks grow up in estuaries and occupy brackish or low-salinity environments farther from the ocean than other shark species.

Research Significance – Despite their large size, preference for near shore habitats, and reputation as one of the most dangerous shark species, the movements of bull sharks have not been well-studied in U.S. waters. This is especially true for their movements within estuaries and into freshwater. As apex predators, bull sharks can influence the movement and habitat use behavior of their prey, which may have trickle-down effects throughout the food web. Some of the species bull sharks interact with in the Chesapeake Bay are targets of economically-important commercial and recreational fisheries. Simultaneous tracking of bull sharks and their prey species may reveal whether their interactions influence which parts of the bay they inhabit.

More Information

Blue Crab Spawning Migration

Every summer, blue crabs migrate north in the Chesapeake Bay to spawn. Once females have spawned, which they only do once in their lifetime, they migrate back down to the lower Bay area to lay their eggs. Our lab is using a combination of mark-recapture and shell-chemistry analysis to learn more about which nurseries these female crabs are coming from. The best way to help sustain a healthy abundance of blue crabs is to protect the spawning females. What we learn from this study may help managers target their efforts.

Cownose Ray Habitat Use and Migration

Video edit by Cosette Larash and Claire Mueller

Cownose Rays are a native, migratory species of eagle ray that visit the Chesapeake Bay from May to October. Little is known about their behavior within the Bay and about their migration habits along the US Atlantic coast. With the help of acoustic telemetry, we are learning how these creatures use coastal habitats and whether they are part of a local, regional, or coast-wide population. This information, in turn, will help inform management of Cownose Ray populations.

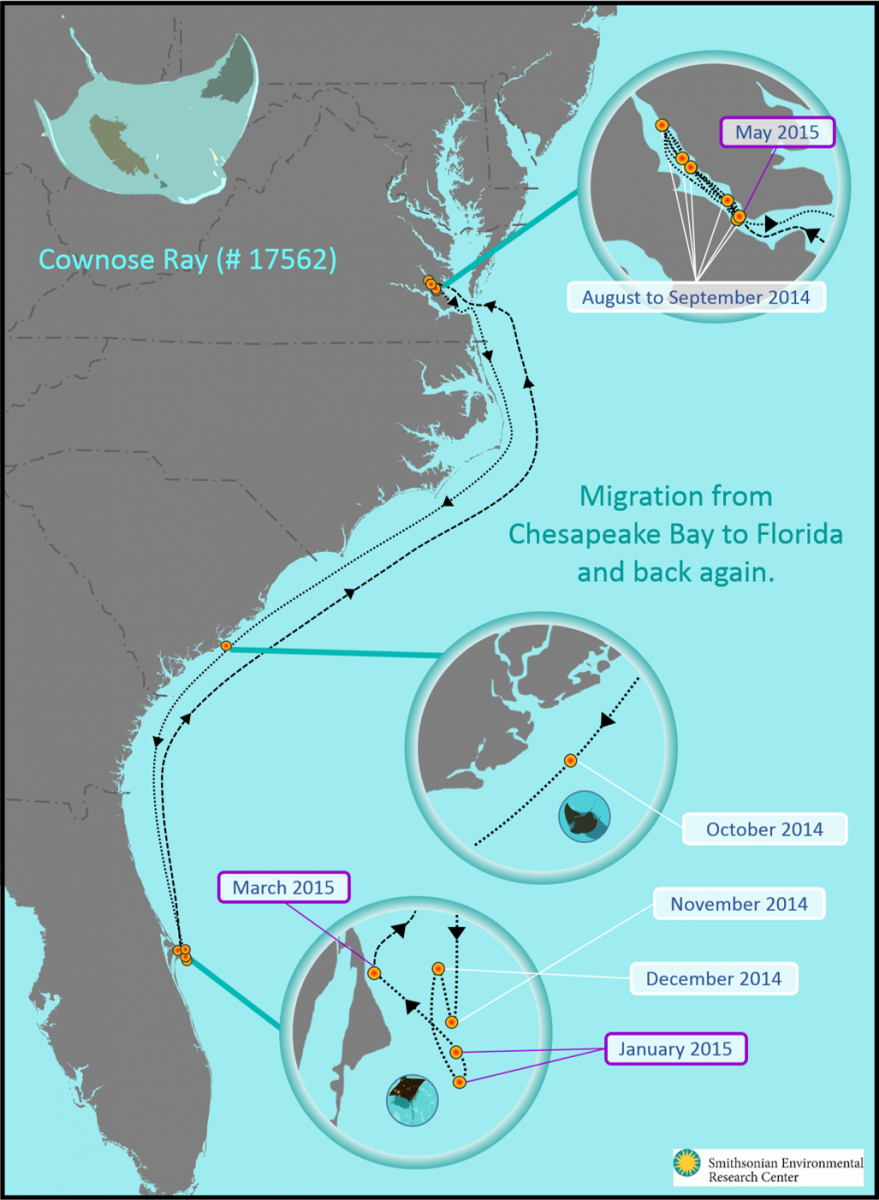

Early results are showing that Cownose Rays tagged during summer in Chesapeake Bay spend the winter along the Atlantic Coast of Florida. When they return to the bay the following summer, they often return to the exact same location where they were tagged. The map below shows the first full annual migration track for a Cownose Ray from Chesapeake Bay. The ray was tagged with an acoustic tag and data were obtained from researchers participating in the Atlantic Cooperative Telemetry Network.

River Herring Spawning Migrations

River herring are anadromous species of fish, meaning that they live much of their life in the ocean, but then migrate to freshwater to spawn. These two species, Alewife Alosa pseudoharengus and Blueback Herring Alosa aestivalis are migratory fish used to be among the most abundant fish in the Chesapeake Bay, but in the past few decades their populations have declined over 90% due to habitat loss, overfishing, and other causes. Our lab is studying the spawning migrations of the river herring populations that visit the Chesapeake Bay tributaries every spring. These studies include using PIT tagging to track individual fish movements within a river system. Tracking movements helps us learn how long individual fish spend on the spawning grounds, whether they return to the same sites each year, and what the survival rate is from year to year.

Interested in learning more about about the Conservation of River Herring Spawning Runs? Click here!

SERC Acoustic Receiver Arrays

One method of studying aquatic animal movement, including behavior and migration, is through the use of acoustic telemetry. Acoustic telemetry involves the implantation of acoustic transmitters into individual animals or attaching transmitters externally. The sound signal produced by the transmitters can then be picked up by stationary acoustic receivers (hydrophones or underwater microphones) that are positioned strategically to detect the tags. SERC maintains arrays of receivers in the Rhode and Patuxent Rivers that we monitor and use to help track species such as cownose rays, blue catfish, and common carp.