We focus on understanding the responses of animals to rapid environmental changes, including land use change, and how conservation actions can maintain biodiversity in the context of these stressors. Often viewing global change through the lens of thermal ecology, we study (1) how drivers of change redistribute individuals and species across space; and (2) how this information can improve conservation interventions like restoration and species management. We address these challenges through a combination of experiments, landscape-scale field studies, and quantitative synthesis.

Ultimately, we aim to bridge the gap between research and conservation implementation through engagement with our local and international partners (e.g., IUCN and Conservation International) and communities of practice, such as the Working Land and Seascapes initiative.

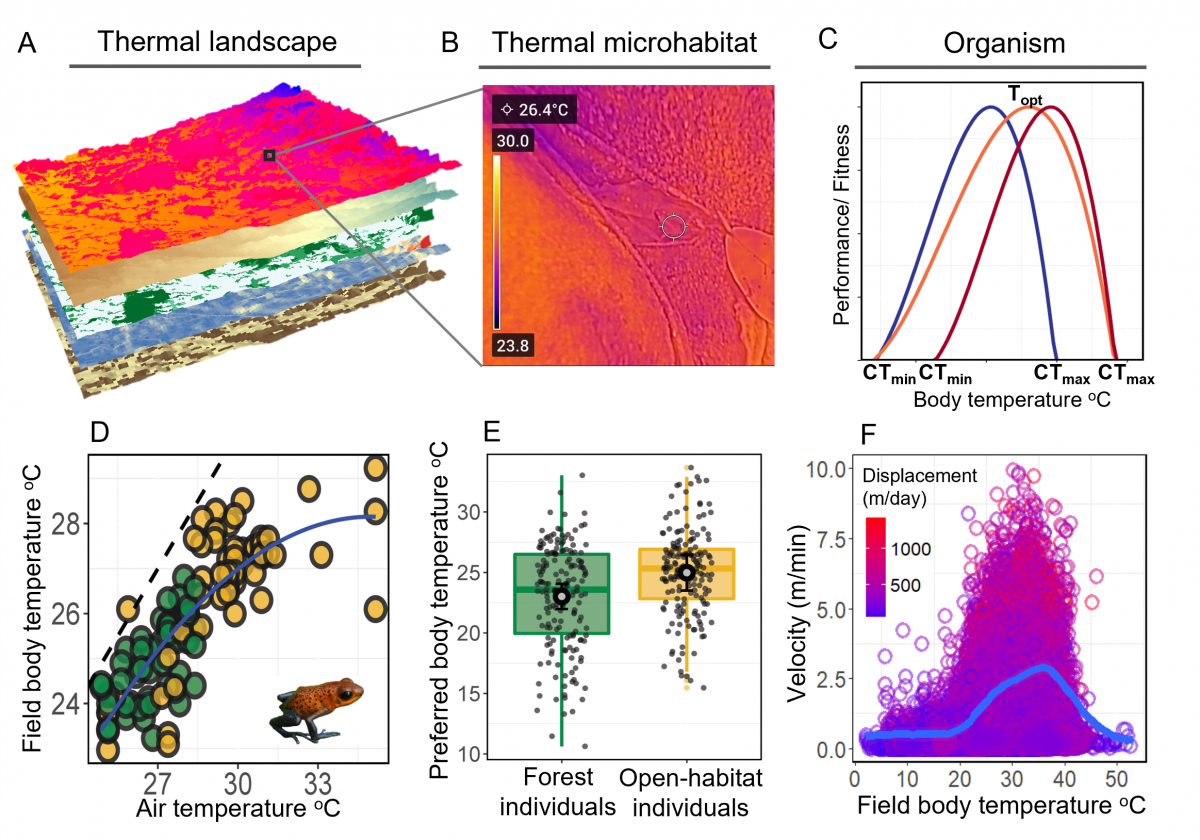

Redistribution of species in changing thermal landscapes

Temperature and moisture affect nearly all aspects of life on Earth. Rapid environmental changes are reshaping spatial and temporal dynamics of microclimates that influence myriad ecological processes, including the redistribution of species. Much of what we know about species-climate relationships is based on coarse climate data (e.g., 1 km2) from far flung weather stations. However, these data do not capture fine scale variation caused by vegetation, topography, and other factors that shape microclimates, the conditions animals actually experience.

The interplay among (A) land cover, (B) local microclimates, and (C) species’ climatic niches (hypothetical thermal performance curves – TPCs – of different species) influences how ectothermic species are distributed across changing thermal landscapes (Nowakowski et al. 2018: Ecology Letters). (D) Exposure of amphibians to temperatures across forest (green) and open land cover types (yellow) can lead to (E) divergence in thermal traits like preferred body temperatures (selected in thermal gradients). (F) Movements of ectothermic species are highly temperature dependent and can scale to patterns of individual space use across time.

To characterize changing microclimates across landscapes, we use a combination of sensor arrays and remotely sensed data, such as LiDAR.

Nowakowski AJ, Peaden JM, Tuberville TD, Buhlman KA, Todd BD (2020) Thermal performance curves based on field movements reveal context-dependence of thermal traits in a desert ectotherm. Landscape Ecology 35:893-906.

Rivera-Ordonez JM, Nowakowski AJ, Manansala A, Thompson ME, Todd BD (2019) Thermal niche variation among individuals of the poison frog, Oophaga pumilio, in forest and converted habitats. Biotropica 51:747–756.

Nowakowski AJ, Frishkoff LO, Agha M, Todd BD, Scheffers BR (2018) Changing thermal landscapes: merging climate science and landscape ecology through thermal biology. Current Landscape Ecology Reports 3:57-72.

Nowakowski AJ, Watling JI, Thompson ME, Brusch GA, Catenazzi A, Whitfield SW, Kurz DJ, Suarez-Mayorga A, Aponte-Gutiérrez A, Donnelly MA, Todd BD (2018) Thermal biology mediates responses of amphibians and reptiles to habitat modification. Ecology Letters 21:345-355.

Nowakowski AJ, Watling JI, Whitfield SM, Todd BD, Kurz DJ, Donnelly MA (2017) Tropical amphibians in shifting thermal landscapes under land use and climate change. Conservation Biology 31:96-105.

Nowakowski AJ, Whitfield SM, Eskew EA, Thompson ME, Rose JP, Caraballo BL, Kerby JL, Donnelly MA, Todd BD (2016) Infection risk decreases with increasing mismatch in host and pathogen environmental tolerances. Ecology Letters 19:1051-1061.

Diversity of responses to global change

Drivers of landscape change create spatially complex and novel conditions for native species. Some species have the capacity to adapt or persist under these new conditions, whereas others do not. By looking across taxonomic groups and spatial scales, We try to identify general principles that explain why many species decline while others persist or even thrive under rapid environmental change. For example, amphibians that decline (blue) or persist (green and yellow) after natural habitats have been converted to human land uses tend to come from the same branches within the tree of life (Nowakowski et al. 2018, PNAS). Tolerant species share traits that likely predispose them to life in converted habitats (Nowakowski et al. 2018, Ecology Letters).

Huang Q, Bateman BL, Michel NL, Pidgeon AM, Radeloff VC, Heglund P, Allstadt AJ, Nowakowski AJ, Wong J, Sauer JR (2023) Modeled distribution shifts of North American birds over four decades based on suitable climate alone do not predict observed shifts. Science of the Total Environment 857:159603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.159603

Murray A, Nowakowski AJ, Frishkoff LO (2021) Climate and land-use change severity alter trait-based responses to habitat conversion. Global Ecology and Biogeography 30:598:610.

Nowakowski AJ, Frishkoff LO, Thompson ME, Smith TM*, Todd BD (2018) Phylogenetic homogenization of amphibian assemblages in human-altered habitats across the globe. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115:E3454-E3462. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1714891115

Nowakowski AJ, Thompson M, Donnelly MA, Todd BD (2017) Amphibian sensitivity to habitat modification is associated with population trends and species traits. Global Ecology and Biogeography 26:700-712.

Kurz DJ, Nowakowski AJ, Tingley M, Donnelly MA, Wilcove D (2014) Forest-land use complementarity modifies community structure of a tropical herpetofauna. Biological Conservation 170:246-255.

Watling JI, Nowakowski AJ, Donnelly MA, Orrock JL (2011) Meta-analysis reveals the importance of matrix composition for animals in fragmented habitat. Global Ecology and Biogeography 20:209-217.

Conservation evidence

Conservation science is a relatively young discipline. As a result, there is still limited understanding of what generally works and why. This problem stems from a lack of standardized and reliable evidence underpinning many conservation interventions. Working with landowners and implementing partners, our lab contributes to conservation evidence through impact evaluation and synthesis. We focus on understanding the impacts of interventions – including habitat protection and restoration – on vertebrate populations, assemblages, and potential co-benefits.

Nowakowski AJ, Deichmann JL, Connette G, Barata IM, Basham EW, Bower DS, Lau MWN, Olson DH (2024) Chapter 10. Surveys and monitoring: challenges in an age of rapid declines and discoveries. In Amphibian Conservation Action Plan: A status review and roadmap for global amphibian conservation. IUCN SSC Occasional Paper, No 57. https://doi.org/10.2305/QWVH2717

Canty SWJ, Nowakowski AJ, Cox CE, Valdivia A, Holstein DM, Limer B, Lefcheck JS, Craig N, Drysdale I, Giro A, Soto M, McField M (2024) Interplay of management and environmental drivers shift size structure of reef fish communities. Global Change Biology 30: e17257. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.17257

Cheng SH, Costedoat S, Sigouin A, Calistro GF, Chamberlain CJ, Lichtenthal P, Mills M, Nowakowski AJ, Sterling EJ, Tinsman J, Wiggins M, Brancalion PHS, Canty SWJ, Fritts-Penniman A, Jagadish A, Jones K, Mascia M, Porzecanski A, Zganjar C, Muñoz Brenes CL (2023) Assessing evidence on the impacts of nature-based interventions for climate change mitigation: a systematic map of primary and secondary research from subtropical and tropical terrestrial regions. Environmental Evidence 12:21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13750-023-00312-3

Nowakowski AJ, Watling JI, Murray A, Deichman JL, Akre TS, Muñoz Brenes CL, Todd BD, McRae L, Freeman R, Frishkoff LO (2023) Protected areas slow declines unevenly across the tetrapod tree of life. Nature 622:101-106. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06562-y

Nowakowski AJ, Canty SWJ, Bennett N, Cox C, Valdivia A, Deichman JL, Akre TS, Bonilla SE, Coastedoat S, McField M (2023) Co-benefits of marine protected areas for nature and people. Nature Sustainability 10:1210-1218. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-023-01150-4

Brown C, Nowakowski AJ, Keung NC, Lawler SP, Todd BD (2021) Untangling multi-scale habitat relationships of an endangered frog in streams to inform reintroduction programs. Ecosphere 12:e03799. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.3799

Peaden JM, Nowakowski AJ, Tuberville TD, Buhlmann KA, Todd BD (2017) Effects of roads and roadside fencing on movements, space use, and carapace temperatures of a threatened tortoise. Biological Conservation 214:13-22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2017.07.022