Altered Environments: An Artistic Lens on Marine Bioinvasions

A curated portfolio of original prints

Altered Environments is a curated portfolio of original prints by international artists addressing the problem of marine bioinvasions. Invited and assembled by ICMB XI partner artist, professor and printmaker April Flanders, Altered Environments includes the work of 25 artists from the United States and Canada. The project was co-sponsored by the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center's Marine Invasions Research Lab.

Marine invaders are species that have expanded beyond their natural range in the aquatic environment via recognized vectors including ballast water, commercial and recreational boating, accidental and deliberate introductions, and rafting, all of which are either a direct result of human activity or exacerbated by it. In this portfolio, the artists address the breadth of the aquatic environment, both salt and freshwater, as a complex and fragile ecosystem, under daily threat from multiple forces.

Participating artists were asked to consider the many aquatic ecosystems currently affected by bioinvasions, and SERC scientists provided the artists with information about the world's most serious aquatic invaders to draw from as they developed their works.

Altered Environment Artists

Alanna Baird, Tunicate

"I am inspired by the intertidal zone of my shoreline. There I find gifts exposed by the receding water, the tiny creatures, who inhabit this shared littoral landscape, offer up their remains. The detritus abandoned by humanity mingles with the organics. My studio practice is a cross contamination of ideas, materials, and structural explorations that are tied to the sea."

Alanna has been expressing her commitment as an environmentalist through her choice of materials for more than 40 years, and now includes minimizing her carbon footprint through a solar powered studio practice. Her work in recycled metal, her tin fish, have become an invasive species of their own, inhabiting private collections around the world, leaving questions of environmental concerns in their wake. Alanna works in sculpture as well as printmaking.

Lorraine Beaulieu, Altered leisure/Plaisance altéré

This image was obtained through the photographic process of cyanotype, enhanced by the collage of an image of a beach ball.

In this composition, I depict the carelessness and ignorance of the character swimming with his beach ball on the surface of water invaded by green crabs. The invasion of the marine coasts is an almost imperceptible phenomenon from the surface of the water.

Green crabs are just one example of invasive species disrupting marine ecosystems. This species has a serious impact on Canadian and North American coasts and elsewhere in the world. Green crab presence influences activities related to these coastal places such as commercial and sport fishing and boating, but above all, it gives free rein to the erosion of shorelines by destroying the marine flora.

Through creativity and changes of our ways considering this species, could we adapt and make useful the invasion of this crustacean in our coastal environments? For example, the creation of biodegradable plastics from the shells of green crabs (Audrey Moores' research).

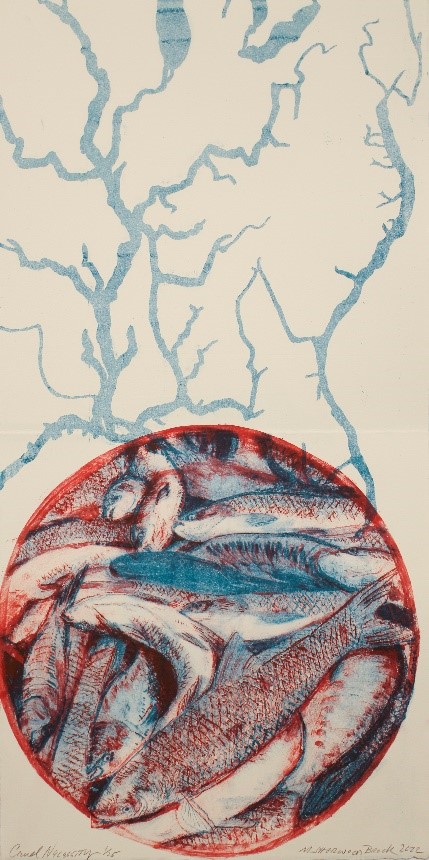

Mary Sherwood Brock, Cruel Necessity

Carps were first introduced in the 1800’s by European immigrants to the waters of North America and quickly became known as an invasive species. They are extremely successful in populating freshwater rivers and streams, where their feeding habits create algae blooms and destroy fragile underwater plants, turning once clear streams into muddy ones. To protect the Great Lakes, a complex system of dams has been set up to contain the varieties of carp invaders and a yearly cull of 80% of the population each year to bring them to a manageable population level. It is hard not to note a comparison with the destructive behaviors of this fish and those of humans on their environment over the years. "Cruel necessity" is a mirror of the pain and a warning.

Patterson Clark, Ark

The print employs exotic invasive plants as a vehicle for the dissemination of native plants. From a Chesapeake Bay wetland, stem internodes from Common Reed (Phragmites australis australis) served as fiber for handmade paper holding seed inclusions of nine marsh plants native to the brackish shore. An image of Common Reed was letterpress-printed onto the paper, using an engraved Norway Maple (Acer platanoides) wood block. Black ink was made from soot collected from the burning of dried exotic invasive vegetation. A QR code embedded in the image provides a digital path to a video that focuses on the print, its folding into an origami boat, its launch into the bay and its spread of native seeds. A soundtrack for the video was generated from musical instruments made from the wood of local exotic invasive trees.

Tallmadge Doyle, Algae Bloom Universe

I embarked on this series of etchings, Algae Bloom Universe, while researching invasive species from a microscopic perspective. I have always felt the beauty is in the details. I started to daydream about delicate cycles of microscopic life forms within ocean waters as playgrounds for new visual realities, where color is ethereal, vivid, and brilliant. Where light is unpredictable and form vibrates, allowing access into the abundance and immensity of what is often unseen by human eyes.

I began to consider intricate systems of microscopic ocean life forms simultaneously with the expansive telescopic realm of our solar system. These natural realities, dissimilar in scope yet, at times indistinguishable in form, overlap and intertwine in my imagination.

Beth Fein, Uninvited

Uninvited is a photo etching with chine collé and letterpress debossing. It’s representative of the marine bio invasion of Carcinus maenas (known as green crabs) along the Pacific coast. The landscape image is from Tomales Bay that lies within the San Francisco Bay Area (a hotspot for bio invasions). It is adjacent to the Point Reyes National Seashore. Tomales Bay has a strong oyster culture and is particularly susceptible to invasive species. The circles of color abstractly represent where these non-native green crabs are located along the western coast of California and where the invasions have been most significant. The blind debossing references the shipping routes through the Panama Canal which are one of the sources spreading marine bio invaders.

April Flanders, Prolific Ingress

This print examines Littorina littorea, the common periwinkle snail, a small but potent invader in the intertidal zones of the eastern shores of North America. A ravenous little pest, it uses its radula to scrape algae and plankton off submerged rocks. In doing so, it has created a huge imbalance in native algal species and has negatively impacted the intertidal marsh ecology. Brought in via ballast water, these snails live from 5-10 years and each female can lay 10,000-100,000 eggs every year.

Sheila Goloborotko, Botryllus schlosseri

The Spaniards, lacking building materials but interested in protecting their colonies found a solution in coral mining. They built walls with piedra múcara, a mixture of coral blocks, sand, rock, and powdered shellfish. Such walls illustrate the hurt of colonization: we take someone’s home and make our own.

The span of damage caused by this bloody conquest and colonization chapter never stopped. We crossed other oceans to conquer the following land and destroyed many above-ground and underwater colonies.

We are not alone in this disastrous ecocide. Take the tunicate Botryllus schlosseri, a system formed by many radial clusters of small individuals or zooids—tiny, colorful, star-shaped colonies. They believe in the power of collaborations—their colonies fuse with close partners to gain sovereignty. Together, they comprise a constellation. Its origin is uncertain, but once dragged to other seas, it spread to many remote parts of the world—scattering their own underwater colonization.

Nature has a way of showing us its power when we make ourselves still enough to see its systems, structures, and ultimately, its ability to teach us how to live more in harmony with it, even as we seek to move ahead as a species.

Melissa Harshman, Altered Environments

My print was inspired by other recent print work dealing with white chrysanthemums. White chrysanthemums are often used at funerals and are often symbolic of death and remembrance. In this light, I printed the flowers around the central, magnified image of a marine bio invader. Together these images reflect and symbolize the environmental damage being done around the world. The images are quite beautiful, which can be deceiving when one examines the relationship of the images to the real world.

Marty Ittner, Blue Catfish

Blue Catfish are known for their massive mouths, whisker-like barbels and a deeply forked tail. "Blue Cats" (as the anglers call them) are BIG. And BOLD. Introduced in the 1970s to Virginia tributaries as a recreational fishery, Blue Cats soon ate their way throughout the Chesapeake Bay. Blue catfish are now considered invasive because they feast on native species.

I doubled the paper size to create a diptych and room for a big cat-fish silhouette. It looms large, steeped in the vintage nautical map showing the inlets and tributaries of the Chesapeake Bay "from head of bay to mouth of river." The cat-fish stencil was exposed on top of the photo litho map using cyanotype, a photographic process also used to make blueprints. During the exposure, the cyanotype-coated paper is sprayed with water, creating fluctuating and unexpected results.

Fleming Jeffries, Haunted Hulls

"Haunted Hulls" centers on how marine bio-invasion spreads through hull biofouling. While researching this topic, I was fascinated by the continuous need to manage natural biofilms, flora and fauna that develop in a matter of minutes, days, and weeks on the hulls of ships. I saw this brisk rate of bioaccumulation as a testament of the robustness of life on Earth. Meanwhile, with the exponential growth and reach of human maritime traffic, mariners and ship builders have long devised surfacing materials (pitch, copper, copper oxide, toxic self-polishing paint, biocide...) along with cleaning practices to combat the inevitable bioaccumulation. Rather than going into detail of these human strategies, I decided to depict sunken hulls of old wooden ships, stationary at the sea bottom, covered in a biome, to underline to deep histories of global trade and hull-bioaccumulation.

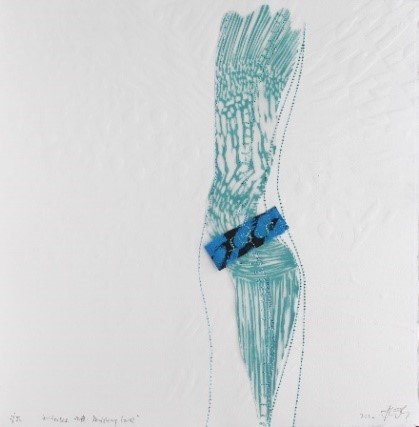

Anita Jung, Lamprey

The Altered Environments print responds to the lamprey as an aquatic invasive species that is a threat to biodiversity and the substance of nightmares. Lampreys have a high reproductive rate, a lack of predators, and an ideal habitat in fresh waters that threaten the Great Lakes. The established population of sea lamprey in these lakes has had a devastating effect on the native fish population. I have utilized materials from craft and hardware stores, every day, and readily available materials along with the creative waste materials generated by the making of unknown things. These found surfaces, repetitive patterns and designs are often fashioned by CNC tools and computers. They embody the cold precision of technology and the grid that then become faltering, vulnerable forms once separated from their intended use. I seek out the hidden patterns that determine, chart, and map our everyday existence and that which disrupts the environment.

Irena Keckes, Undersea World: Vanishing of Coral

Living and working in diverse artistic and scholarly environments in Europe, Japan, USA, New Zealand, and, more recently, Guam has shaped my approach to art making and thinking. My main artistic practice is printmaking. I employ both Eastern and Western print methods, placing an equal importance on concepts and technologies. My art research has been informed by ecologically responsive and expanded forms of contemporary print, and as well aspects of phenomenology, deep ecology, and Buddhist practice and philosophy.

While using one of the oldest printmaking methods, my practice has moved towards what may be called an extended field of print: my large-scale woodcuts are often placed alongside the three-dimensional objects – carved wooden plates. Merging intellectual and physical acts of making, exploring embodied ways of knowing, and mind-body interrelations have been key components of my artistic query.

Eveline Kolijn, Invading Familiars and Strangers

The environmental threat to coral reefs is a personal issue, as I spent my childhood in the 1970’s on the Caribbean Island of Curaçao scuba diving and snorkeling. Reconnecting with the island twenty years later, I found the state of coral reefs severely diminished.

Besides overfishing, pollution and climate change, invading species have had negative impact. Most spectacular is the introduced lionfish (Pterois volitans). Originally from the Pacific, it has been released from aquariums and is a flourishing, voracious, and devastating newcomer.

The sargassum seaweed (Sargassum natans) is endemic to the Caribbean, but fed by fertilizer runoff, it grows out of control and suffocates life around island coasts. Ballast water of ships introduce visible and invisible newcomers, such as bacteria. An infection, stony coral tissue loss disease (SCTLD) is suspected to be caused by one those organisms, devastating already stressed-out coral species.

Lauren Kussro, Beauty Invades

I’m an explorer. Navigating terrain and documenting botanical and geological matter, I’m looking for clues, details that get missed or forgotten. I hold them up to see what they point to and what they convey.

From the micro to the macro, nature provides me with a variety of environments and organisms to investigate and study, and I find perpetual inspiration in seeing how everything is connected and how it works. Systems existing in clusters or groups hold particular interest for me because of the way individual bodies come together to build a larger whole. I use references like densely textured coral reefs, delicate fungal forms, or interlocking cellular structures as a springboard, a place to start creating my own forms.

The complexity of the universe invites exploration and discovery and is part of what I find so appealing – the layers upon layers that wait to be revealed. This layering occurs in physical forms but also appears in our intellect and spirituality. For me the act of creating is closely linked with my faith and is a physical way of investigating my own beliefs through imagery and metaphor.

Ann Manuel, Carcinus maenas

Ann Manuel’s multimedia practice revolves around the themes of physical geography, relationships, identity, and sprituality.

I chose the marine misery known as the European Green Crab. The base layer of this print is an etching with three rainbow roll passes and one photo transfer with chine collé to follow. The text transfer about this invasive hungry crab comes from the book "A Preliminary Guide to the Littoral and Sublittoral Marine Invertebrates of Passamaquoddy Bay" by R.O. Brinkhurst and L.E. Linkletter, et al.

Text in the image reads: Carcinus maenas (Linnaeus), the "Green Crab," up to 80 mm wide, has a granular carapace with very prominent sharp anterolateral teeth. The first pair of legs is stout and terminate in claws. The last pair of legs is flattened with pointed tips. The color varies from greenish-black to orange with numerous yellowish spots. A common shore crab found intertidally to several meters.

Sandra Murchison, Horton Bay

My mixed media prints emphasize the innate tension between how we wish to hold sacred our sense of history, place, and local community; and yet, we seem to lack conservation, exist virtually and experience rapid global warming. Our communities and ecosystems are in jeopardy. In my work, I seek to slow this imbalance.

Traveling in my state of Michigan, I make rubbings of the historical markers. The Horton Bay marker, used in my print of the same name, stands in front of tiny town hall in the hamlet known as Horton Bay on the edge of Lake Charlevoix in northern Michigan. The story on the marker has to do with how this 1876 settlement relied on timber until it was depleted and then fishing for its survival. The cove at Horton Bay is thick with rocks and frequent Zebra Mussels.

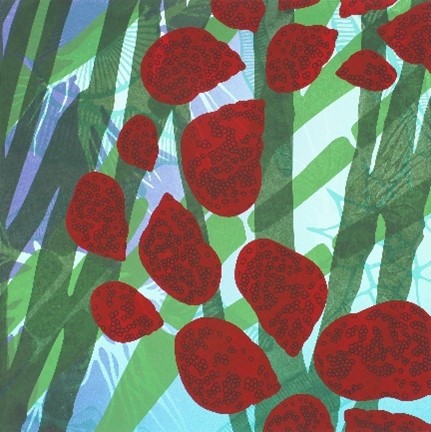

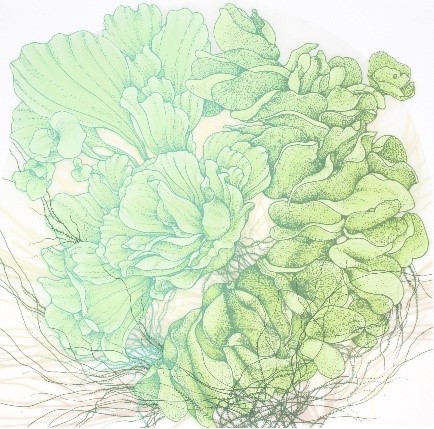

Michelle Rozic, Sargassum horneri: Devil Weed

A CMYK screenprint of a Malibu tidepool shows the calm water surface, churning brown and blue, covering the life teeming within. Overlayed in an artificial aqua is Sargassum horneri, known by Southern California divers as Devil Weed. A weed is an unwanted plant, growing out of place. Many weeds become invasive, pulling resources from, and crowding out native life.

Native to Japan and Korea, the seaweed was first discovered in 2003 in the Port of Long Beach. Experts think it hitched a ride on an international commercial vessel, finding the California ecosystem ripe for multiplying. In less than 20 years, beds of Devil Weed have crowded out native kelp forests as far south as the Baja peninsula and as far north as the San Francisco Bay. Already there is great loss to the local biodiversity, with unknown consequences from the disruption of the once balanced ecosystems.

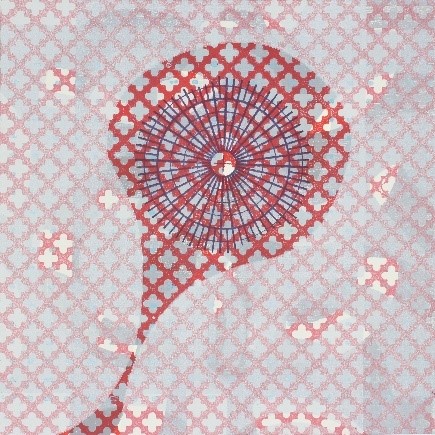

Marilee Salvator, C. mutabilis #1

I am fascinated by the beauty and potency contained in microscopic life forms that are, quite literally, threatening to other life forms. Cellular structures can reproduce, mutate, and spread without regulation. I’ve most recently begun a project based on marine bio-invader imagery, graciously shared with me by marine scientists Thomas Trott and Matthew Dick. With their assistance, I am learning about aquatic invertebrate and bryozoan research and responding through my studio process. The imagery is providing me with a fresh visual language that lends itself well to my formal exploration of repetition, pattern, deeply hidden beauty, destruction, and exponential growth.

C. mutabilis #1 is the first work I created that explores this new direction in creative research. This piece is based on the bryozoan Cribrilina mutabilis (now Juxtacribrilina mutabilis). I was immediately drawn to its delicate form, repetition, and intricate detail. I am fascinated by its beauty and invasive nature.

Rachel Singel, Pacific Barnacle (Balanus glandula)

Introduced species can have tremendous ecological effects and can become a major threat to ecosystems. Through global shipping routes, barnacles have been introduced to coastlines worldwide. An example is the barnacle Balanus glandula, native to the North American Pacific coast and transported by ships to the Pacific coast of Honshu, Japan, where it has replaced several native barnacle species. Furthermore, Balanus glandula has reached as far as the Atlantic coasts of Argentina and South Africa, with negative effects on native barnacle populations and other seafloor dwellers.

This etching of the Balanus glandula is printed on paper made from another invasive, yellow flag iris (Iris pseudacorus). Yellow flag iris, native to Europe, outcompetes native riparian vegetation, including cattails, sedges, and rushes, and it degrades native fish habitat, as well as bird nesting and rearing sites.

Tanja Softic, Mnemiopsis leidyi

I encountered Mnemiopsis leidyi last year, in the Adriatic Sea, far from its natural habitat (subtropical Atlantic estuaries). When I jumped in, I anticipated the usual cool, bracing sensation that would quickly yield to the pleasure of swimming in perfect, buoyant, salty blueness—a mainstay of my childhood summer pleasures. Instead, it felt like swimming in tapioca pudding. Millions of translucent, ovoid creatures amassed along the shore, released by illegal ballast water discharge by a cruise. A food source for birds and fish in its native habitat, it has no natural predators in the Mediterranean Sea. Its appetite for zooplankton has already nearly destroyed fisheries in Azov and Black Sea.

This print started with a vague intention of revenge for my destroyed swim—as I researched more, I came to feel compassion for Mnemiopsis ledyi—another trafficked immigrant, blamed for human carelessness and greed.

Julie Wolfe, Phyllorhiza punctata

Julie Wolfe's Phyllorhiza punctata illustrates the slippage between the scientific perspective and that of a visual artist, through the medium of silkscreen printing while using color and form her tools.

Performing alongside its peers in a synchronized, fictitious setting, this "Spotted Jelly" is making meaning out of chance and play as well as deconstructing traditional aesthetic conventions of scientific data.

This print edition is, however, grounded in real referents as diverse as environmental degradation based in scientific data and damage caused by humankind, all resulting in severe marine bioinvasions as a conceptual starting place.

Here, the positive is balanced with the negative: the aesthetic with the destructive, the natural with the human, and the image with the abstract. Though not necessarily depicted in harmonious union, opposing forces are explored as equally meaningful.

Julie Wolfe is a multimedia artist living and working in Washington D.C. She is best known for her emergent language of color and form and free association of the subconscious mind and perception. To accompany her large bodies of work, she publishes multiple artists books that are in collections including the National Gallery of Art Library, New York Public Library, and the National Museum of Women in the Arts Library.

Elizabeth Jean Younce, Coastal Southern California

fig.1 Orthione griffenis, [invasive] ectoparasitic isopod • fig.2 Upogebia pugettensis, [native] blue mud shrimp • fig.3 Calidris alpina, [wintering] dunlin • fig.4 Carcinus maenas, [invasive] European green crab • fig.5 Urosalpinx cinerea, [invasive] Atlantic oyster drill • fig.6 Ostrea lurida, [native] Olympia oyster

The green crab Carcinus maenas is a globally damaging invasive species and in Southern California, in particular, it not only decreases native crab populations, increases invasive whelk populations such as the Atlantic oyster drill, increases populations in other invasive clams, but also reduces food abundance for wintering shore birds such as the dunlin. Dunlin often eat native blue mud shrimp, but they too are being negatively impacted by an invasive parasite. Population increases of the invasive Atlantic oyster drill have contributed correlated with decreases of the native Olympia oyster.

Elizabeth Jean Younce’s work is born from the worlds of scientific, medical, and children’s-book illustration, as well as symbology, natural history, wunderkammers, and feminism. While her works take the form of prints, much of Younce’s practice involves the physical collection of natural specimens from forests, prairies, and bodies of water. The lithographic prints serve as psychological investigations of such specimens. Specifically in this Bestiary, the flora and fauna serve to illustrate the dichotomy between their lives and our own human ones. On a most basic level this work is based on the dissection of ideas involving fear and feelings of being overwhelmed, while simultaneously deconstructing what it means to be a fertile being. The evolutionary process of plants and animals metaphorically mirrors our own developments. Instinctual habits of the animal kingdom relate to our "civilized" lives. A mother swan’s capability to fight off a predator can function as a visual metaphor for ways we overcome seemingly impossible situations in our lives. The sheer fact that a fragile, fertile, feathered, female can overcome seemingly impossible situations can function as a visual metaphor for perseverance. The obstacles we struggle to overcome may be great or insignificant regardless this struggle is all-consuming. These conflicts involve questions of identity, equality, self-worth, depression, growth, change, life, and ultimately death. It is these fundamental and undeniable questions that define our humanity.

Simultaneously, there is duality between these symbols and their meanings. While a boar may appear a dangerous, beastly, creature, symbolic tradition would instead lead one to believe that the boar represents fertility as well as motherhood and all of the patience, nurture, and care that it requires. So much of perception is taught or learned yet, when we take a second look... things are not always what they seem. These creatures are beautiful, delicate, yet strong and capable of survival. We all are wild and fragile beings; we have similar wants, needs, and desires. Our bodies are incredibly resilient yet can fail us instantaneously. By warping or perverting the flora and fauna referential of fairytales or children’s books, we peer into the psyche of Mother Nature.

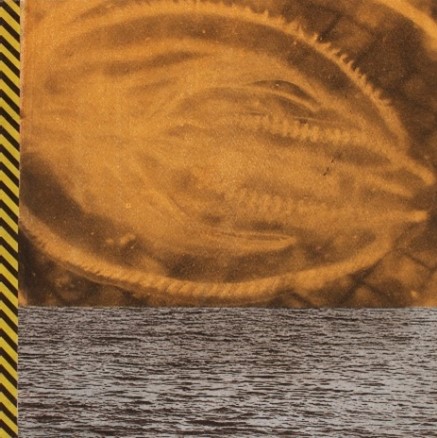

Anna Zellhofer & Caroline Zellhofer Hunter, Caretaker

In the spring of 1959, the Haplosporidium nelsoni parasite, or MSX, was introduced to the US East Coast and Chesapeake Bay. In just 3 years, MSX affected 90% of lower Chesapeake Bay oysters, causing massive mortalities of the keystone species. Harvests have dropped from 3,000,000 bushels in the Bay annually during the 1950s, to just 6,000 in 1993. MSX endangers the multi-generational livelihood of oyster farming and our community which thrives on a healthy Bay.

The outline of an MSX-infected oyster cradles the image of a hard-working oyster farmer, a representation of our community, history, culture, and traditions. The edge of their silhouette fights against the encroaching MSX, taken from microscope images in Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) publications. We are completely intertwined with the health of the Bay. When we lose keystone species to invasive organisms like MSX, we lose something of ourselves. We are called to be caretakers of the oysters and our environment; we all must care for our environment on a personal, community, and governmental level, or we risk losing everything.