Strategy To Flush Invaders From Ballast Water Coming Up Short

In the battle against invasive species, giant commercial ships are fighting on the front lines. But even when they follow the rules, one of their best weapons is coming up short, marine biologists from the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) discovered in a new study published in PLOS ONE Monday.

As ships move goods around the world, they often inadvertently ferry invasive species as well. These new species can come over in the ships’ ballast water—the water ships pump on board for stability, to keep them from becoming top-heavy. But when the ships arrive to port, they often discharge their ballast water from distant global regions, along with the unseen, unwanted hitchhikers.

Shipping companies and biologists have known about this problem for decades and are still struggling to combat it. Currently, their main strategy is called “open-ocean exchange.” The idea is to flush out ballast water from their original port in the open ocean, to remove most coastal organisms, and replace it with water more than 200 nautical miles from shore. When they arrive at their destinations and discharge their new ballast water, any open-ocean organisms they picked up are unlikely to survive in ports and coastal waters.

“Ballast-water exchange provides a stop-gap measure until new technologies can be implemented to further reduce species transfers,” said Greg Ruiz, SERC senior marine biologist and a co-author of the new study. Since 2004, the U.S. Coast Guard has required most commercial ships entering the U.S. from overseas to do open-ocean exchange before discharging ballast in ports. However, this strategy has some serious limitations and may not be as effective as scientists and policymakers once hoped.

Ruiz and a team of SERC biologists led by Jenny Carney examined the ballast water of large bulker ships entering the Chesapeake Bay for a period of 20 years, comparing samples from vessels before the open-ocean exchange rule went into effect to those from afterward. All the later ships they sampled had performed open-ocean exchange, while the earlier group had not. But instead of going down, the concentrations of potential coastal invaders scientists found in ballast water were five times higher in recent ships, despite the routine use of open-ocean exchange.

“We were surprised that we found more organisms in our samples.…We were expecting the numbers to be lower,” Carney said. One possible explanation is that the water ships are taking in today has more organisms to start out with—making it harder for ballast-water exchange to get rid of them all. It is also possible more organisms could be surviving the journey to the Chesapeake, a scenario made more likely by shorter voyages.

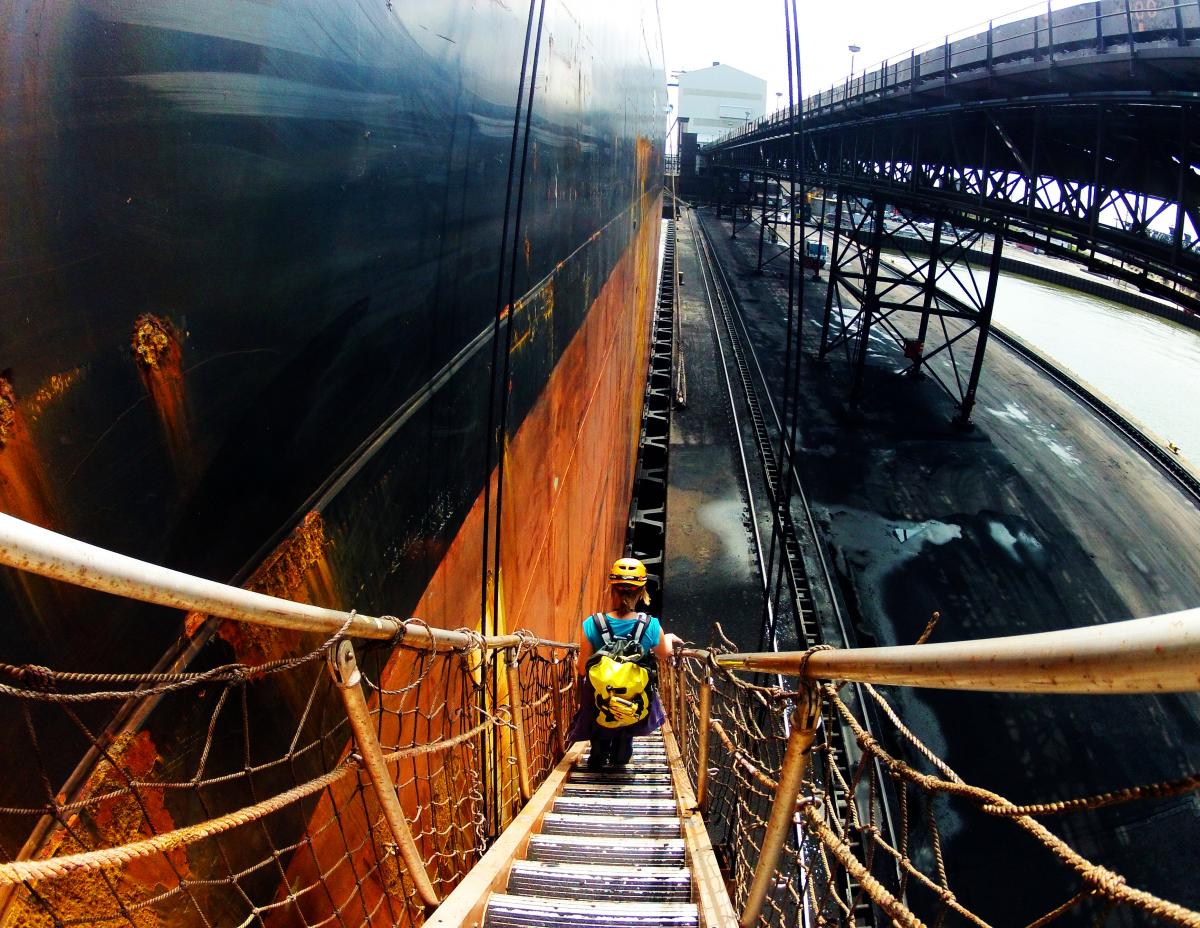

The authors noted other changes as well, largely associated with the coal trade. Besides increases in the concentration of ballast-water organisms, the total volume of ballast water discharged in the Chesapeake is also spiking. Overseas ships have discharged almost five times more ballast water into Chesapeake Bay in 2013 compared to 2005, when open-ocean exchange was adopted. Most of that increase came from bulkers, massive cargo ships that transport coal and other bulk products in one direction, and return loaded with overseas ballast water from elsewhere in the world. From 2005 until the end of the study, the more coal the Chesapeake exported, the more bulkers came into its ports.

This does not mean open-ocean exchange does not work, the authors point out, but rather that it is facing unprecedented difficulties. “The shift in trade is counteracting the real effect of ballast-water exchange,” Ruiz said. The surge in global trade is causing increases in the two critical measures that determine how many potential invaders arrive in the Chesapeake: the concentration of organisms in ballast water and total ballast water discharged in the bay.

Instead of exchange, a more effective solution is emerging for ships: using onboard technology to eradicate invaders. SERC ecologist Ian Davidson, who was not part of this study, published another study earlier this year outlining the early patterns of treatment systems on some ships, using methods like ultraviolet radiation.

“In exchange, you can have even 90 percent efficacy, but if you have a lot of organisms at the start, you’ll still have 10 percent of a lot of organisms,” Davidson said. “For ballast treatment, no matter how many organisms you have at the start, it is expected to reduce those down to no more than 10 per cubic meter for the largest size class.”

The U.S. Coast Guard has set new discharge standards for treatment technology that would overcome limitations of open-ocean exchange, and it has already officially approved three treatment systems for ships to use onboard. In addition, 54 nations have signed the Ballast Water Management Convention, which sets limits for the global fleet on the highest concentrations of various organisms ships can have in their ballast water before discharging it. These limits will be phased in starting in September 2017. The battle against invasive species is now shifting toward developing the new technologies—and enabling ships to adapt to them.

To learn more about the study or speak to one of the authors, contact Kristen Minogue at minoguek@si.edu or 443-482-2325. A copy of the full study is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0172468.